May 26, 1647

Massachusetts Bay Colony Bans Catholic Priests

On this day in 1647, Massachusetts Bay banned Jesuit priests from the colony on penalty of death. The English Puritans who settled the colony feared the Jesuits for several reasons. First, simply because they were Catholic. To Puritans, Catholicism was nothing less than idolatrous blasphemy, and Catholics were destined for eternal damnation. Second, because the Jesuits were French, and France and England were engaged in a bitter struggle for control of North America. Finally, Jesuit missionaries had converted large numbers of Indians in Canada to Catholicism. Indian converts were potential allies of France and enemies of the English. Although no Jesuit was executed for defying the ban, the legacy of anti-Catholicism in Massachusetts survived for generations.

Samuel Adams proclaimed that "the growth of Popery" posed an even greater threat than the hated Stamp Act.

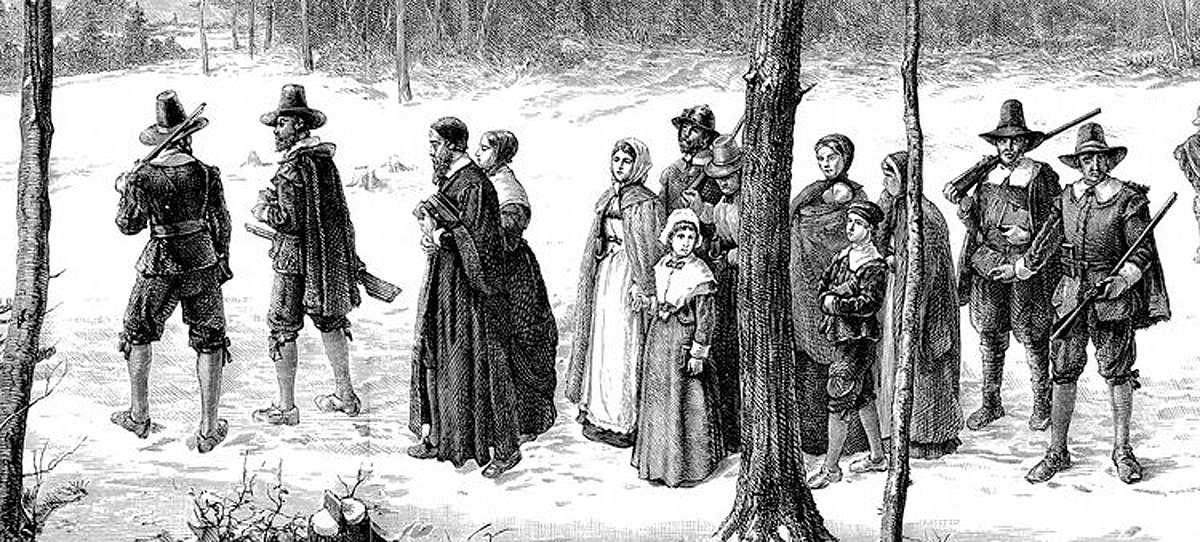

The English Puritans who settled Massachusetts in the 1630s feared dangers lurking in the vast new land. What frightened them most was not hostile Indians or wild animals. In the woods to the north and west were people they perceived as "devils" — Roman Catholic Frenchmen and their Jesuit missionary priests.

The Puritans were horrified to find that Jesuit missionaries working in the French provinces were successfully converting Indians and, even worse, English captives to Catholicism. Puritans believed that Catholic converts were destined for eternal damnation. To prevent the spread of Catholicism into Massachusetts Bay, the General Court banned Jesuit priests from entering the colony.

While the Puritans were inhospitable to anyone who did not share their religious views, they were particularly hostile to Roman Catholics. Puritans had originally separated from the Church of England because they believed it had not cleansed itself fully of "corrupt" Catholic practices. They "purified" worship by eliminating rites, rituals, and outward signs of religion such as crucifixes, holy water, statues, priestly vestments, and stained glass. They also rejected church hierarchy and abolished the priesthood. To them, the Pope was the "Antichrist," and the "Papists" who followed him were in league with the devil.

Puritans had originally separated from the Church of England because they believed it had not cleansed itself fully of "corrupt" Catholic practices.

The French had begun staking out claims even before the English arrived in Plymouth. Like their countrymen at home, the French who established trading posts at Quebec in 1608 and Montreal in 1642 were Roman Catholics. They brought with them Jesuit priests, members of a Catholic order that promoted education as the best way to spread Catholicism. The Jesuits had considerable success converting Huron and Algonquin Indians. As the French missionaries pushed south as far as the Kennebec River in present-day Maine, the Puritans saw a double threat on their border. These men were not only Catholic, they were French, and France and England were already struggling for dominance of the North American continent. With its territory in Maine, Massachusetts was the northernmost English colony. The French Catholics were an all-too-real threat.

The first Jesuit missionary made several trips along the coast of what is now Maine in 1611, almost 20 years before the Puritans settled in Boston. Others followed. In 1646 a French ship visited Boston with two priests on board, and the colonial governor entertained them at his home. The General Court did not approve of the governor's hospitality. The next year lawmakers banned Jesuit priests from the colony.

Only a handful of Roman Catholics resided in Boston in these years. According to a 1689 report, there was not a single "Papist" living in New England. But in the early 1700s, stories began circulating that there were "a considerable number" of Catholics in the colonial capital. During the winter of 1732 a newspaper reported that an Irish priest had celebrated Mass "for some of his own nation" on St. Patrick's Day. Bostonians were alarmed enough for the governor to order the sheriff and constables to break into homes and shops and arrest any "Popish Priest and other Papists of his Faith and Persuasion." While English and French soldiers were fighting in what came to be called the French and Indian War, authorities in Boston arrested 100 French Catholics "to prevent any danger the town may be in."

Bostonians were alarmed enough for the governor to order the sheriff and constables to break into homes and shops and arrest any "Popish Priest and other Papists of his Faith and Persuasion."

Even after the end of the war, Bostonians did not let down their guard. Each year, Harvard College sponsored a lecture against "popery." In 1765, the lector prayed, "May this seminary of learning, may the people, ministers, and churches of New England ever be preserved from popish and all other pernicious errors." Three years later, Samuel Adams proclaimed that "the growth of Popery" posed an even greater threat than the hated Stamp Act. As late as 1772 Boston specifically prohibited "Roman Catholicks" from practicing their religion because it was "subversive to society."

The Revolution forced Massachusetts to change its stance towards, if not its view of, Catholics. An alliance with France was critical to the success of the American cause. From his Cambridge headquarters in 1775, George Washington objected to the celebration of "Guy Fawkes Day" — the anniversary of a failed 1644 Catholic uprising in England. Washington was incensed that there should be "officers and soldiers in this army so void of Common sense" as to insult the Canadians and French, the new nation's potential allies. After independence, some French soldiers chose to remain in Boston, creating the core of the first Catholic congregation in New England. Mass was celebrated publicly in the city for the first time on November 1, 1788.

". . . it is wonderful to tell what great civilities have been done to me in this town, where a few years ago a Popish priest was thought to be the greatest monster in the creation."

When Rev. Fr. John Carroll, the Bishop of Maryland, visited Boston in the spring of 1791, he wrote home that "it is wonderful to tell what great civilities have been done to me in this town, where a few years ago a Popish priest was thought to be the greatest monster in the creation." The Bishop estimated that there were then about 120 Catholics then living in Boston.

Under the leadership of two French priests who arrived in the 1790s, the Catholic Church took root in New England. Over the next ten years, the Catholic population of Boston grew to about 500. When John Carroll visited again in 1805, he decided it was time for the city to have its own bishop. In April 1808, he appointed the Rev. John Louis de Cheverus the first Bishop of Boston.

Anti-Catholic sentiment did not disappear with the growth of the Catholic population. Indeed, the huge wave of Irish Catholic immigration after 1840 brought a renewal of prejudice, discrimination, and even violence against Catholics. It would be more than a century before anti-Catholic sentiment would finally begin to fade. Eventually, a son of Massachusetts would become the nation's first Roman Catholic president.

No comments:

Post a Comment